¿Dónde está el estado?

Flooding devastates the community of Pogue in western Colombia vf

In June 2025, around 34,000 families in western Colombia were hit by devastating floods. Hundreds of these families have also been affected by the ongoing armed conflict. For many, this isn't a new ordeal.

Despite the efforts of the authorities, some families stand as beacons of resilience amidst such adversity.

Read and watch the inspiring story of the community of Pogue.

“The day began to darken, the temperature dropped, the weather turned, and at six in the evening, it started to rain.”

“By eight o'clock, the storm had begun. Inside the house, we sat, we laid down, we got up - listening to the thunder and lightning. The rain didn't stop. The darker it became, the heavier the rain fell. Around three in the morning, I said to my husband: ‘Go and check the boat on the river’. He went and told me: ‘The river is much deeper now’.

“We got up, and I woke up my daughter and son-in-law to because the river was rising rapidly.

“When dawn broke, the river was already inside the house.”

This is how Florentina Rivera, a farmer from western Colombia, remembers the night her village flooded in November 2024.

Within hours

That night changed the lives of all the families in Pogue village. The rain caused the rivers to rise quickly and overflow. Within hours, the water swept away their belongings, crops, animals, boats, and homes.

“Fortunately, we are alive, but it was a very difficult situation for the community,” says Marcelina, one of the community leaders. “We lost everything. We lost our crops, our cooking pots, fishing boats, and our animals.

“The river rose with great force. We tried to gather our belongings, but we couldn't - we had to save the children and leave our things behind. We found shelter on higher ground above the community, where the school, the health centre, and the church are located. We spent several nights there.”

The disaster brought hunger and illness in its wake. Food supplies ran out, the local health centre had no essential medicines, and government aid never reached this remote and hard-to-reach corner of western Colombia.

“We were deeply saddened at that point,” continues Marcelina. “We genuinely feared for our lives. The river had flooded before, but never had the water entered our homes. We kept asking ourselves: ‘if it rises any higher, what will become of us?’ The children were crying, and I was crying too.”

Erasmo Izquierdo, a farmer who has lived in Pogue for 39 years, suffers nightmares because of the flooding. When it rains, he finds it difficult to sleep. Erasmo, like many other residents of Pogue, also cannot stop thinking about what he had lost in the flood.

More than 45 families lost their homes entirely, but the damage extended far beyond that.

In late 2024, flooding in Chocó, western Colombia, impacted over 200,000 people, with thousands already suffering the effects of armed conflict.

Deprived of food and aid

“The heavy rains damaged the plantain crop and other crops. The river rose so much it submerged everything,” says Luis, a local fisherman who lost all he had.

For the families in the community, plantain is a primary food source and their economic lifeline. Seeing their plantain crops submerged in water filled the community with fear and uncertainty.

A single plantain plant takes 10 - 12 months to mature, meaning recovery in these circumstances would take a long time. For many, it seemed out of reach.

“The floodwaters wiped out my plantain plantation, my cassava crop, and even some chickens we relied on for food,” says Luis. “We sell plantains to buy what we need to eat. Our survival depends on it - we've always lived by growing plantains.”

Anxiety intensified, and the community found no answers.

“We requested help from the government, but assistance did not arrive,” continues Luis.

Recovering the crops and, more importantly, restoring their productivity could take years. The floodwaters and landslides didn’t just destroy the harvest, but they also swept away fertile soil and essential farming tools.

The flooding also damaged the community’s water supply system. “The only thing that gave us clean drinking water in the community completely disappeared,” says Luis.

When the water supply system failed, waterborne diseases quickly spread. Diarrhoea, stomach pain, rashes, itching, and fever became common. With no medicine available at the local health centre, the situation grew even more dire – especially for children. Reaching the nearest health facility, hours from Pogue, was not a viable option.

Caught between floods and armed conflict

Armed conflict has also cast a long shadow over the community of Pogue. It has driven families from their homes, silenced daily life, and left people confined and threatened.

“These have been difficult situations - we never imagined we would be forced to flee our homes,” recalls Marcelina. “People were in tears when we fled. Arriving in another community that isn't your own is very hard. There's no trust, and you feel rejected.”

Some time after being forcibly displaced, the community returned to their land, but non-state armed groups have maintained a presence in the area ever since. In Colombia, over nine million people live under the influence of non-state armed actors.

In 2024, before the flooding, the population was forced into confinement.

Trapped

Confinement is a strategy employed by non-state armed actors to exert control. The logic is simple: whoever controls the population, controls the territory and its illicit economies. These groups use threats, anti-personnel mines, homicides, sexual violence, armed violence, and curfews to keep communities inside their homes and rival groups out.

In 2024, 138,000 people across Colombia were subjected to confinement - the highest figure reported since 2008. The situation has not improved in 2025. In the first two months of the year alone, tens of thousands more forced into confinement. The violence restricts access to food, healthcare, and education. Children are often unable to walk to school. Medical treatment is out of reach.

“We live in fear all the time because armed people come into the area,” continues Marcelina. “There are armed people along the river all the time. It's very hard. It's upsetting. There are moments when you just want to break down and cry, but you have to hold it together. As a farmer, the thought of going to the city brings up the worry of where would we find work.”

Beyond the violence, the lack of state presence, soaring fuel prices, and fear of armed conflict all contribute to the community’s isolation. These barriers prevent residents from seeking medical care, humanitarian assistance, or even securing parts to repair the local water system.

Starting over

Despite the absence of support and the significant challenges they faced, families in Pogue began to rebuild, replanting crops and repairing homes. With little access to formal healthcare, they turned to traditional medicine and jungle herbs to care for their health. Aid from the international community soon arrived, bringing tools for farming, food during times of scarcity, dry clothing, and materials to reconstruct their houses. Water filters were distributed to improve access to safe drinking water, and healthcare assistance played a crucial role in restoring the wellbeing of the community.

Construction workshops were also held to train residents in rebuilding techniques and to share vital healthcare information.

Despite repeated promises from Colombian authorities, the community is still waiting to be relocated. For years, they have called for resettlement, citing due the risky conditions in which they live. The Colombian Inspector General's Office has called on the national government to ensure the fundamental rights of the Pogue community, including access to safe housing, land, and a dignified life.

“Don't forget our farming children, or the community of Pogue,” urges Marcelina.

“Even if it only happens for my grandchildren.”

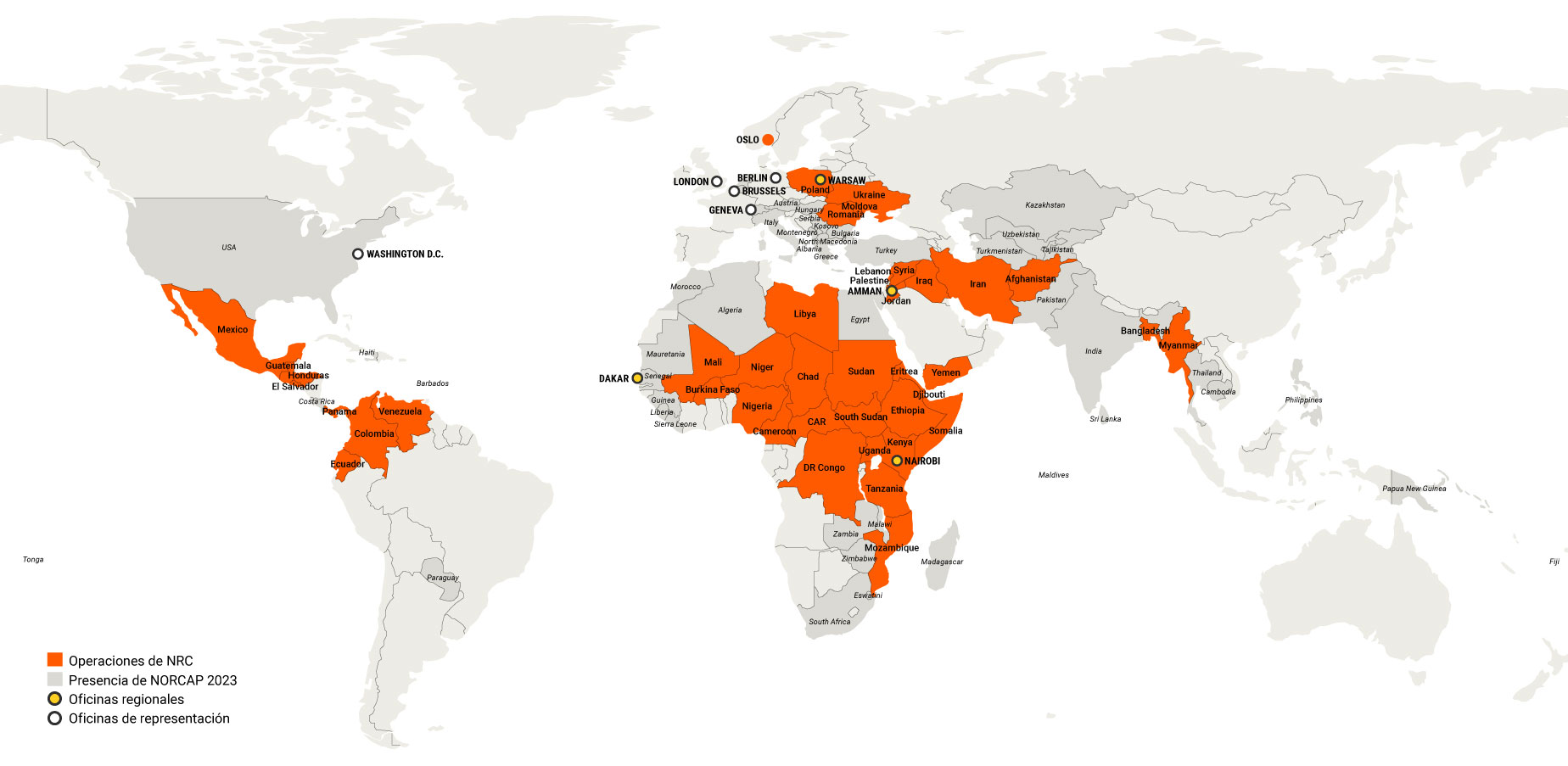

Starting over was made possible through the support of the humanitarian action of the MIRE+ Consortium, funded by the European Union, the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and led by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

The needs of the population persist, and it is urgent that local, regional, and national authorities establish a presence and address the situation of the Pogue community.

Furthermore, the recent declaration of an emergency in June 2025 further exacerbates the already dire situation many are facing in this western department.

“The future I dream of - for myself and the whole community - is to be relocated, to move away from this plot of land, because we are in a high-risk area,” says Marcelina. “That's the most beautiful future, even if it only happens for my grandchildren.”