A life

in ruins

Al-Mawasi, in the southern Gaza Strip

Ziad al-Nada, 44, has always lived in Al-Mawasi, a narrow strip of sandy land stretching 14 kilometres along the southern Gaza Strip. He made a home here with his wife, Maha, and their five children, living in a neat apartment just a few hundred metres from the beach.

Ziad and his children, Salma (14), Serene (6), Abed (12), Mohamed (17) and Adam (18). Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Before the escalation in hostilities, life for Ziad and his family was “normal”, at least by the standards of an enclave that had been subject to an Israeli-imposed sea and air blockade and land closure since 2007.

“Despite Israel’s closure of the Gaza Strip and the many associated difficulties, we secured and provided for a respectable life,” Ziad told NRC in June 2024.

“We were always able to create something from nothing.”

Ziad and his children, Salma (14), Serene (6), Abed (12), Mohamed (17) and Adam (18). Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad and his children, Salma (14), Serene (6), Abed (12), Mohamed (17) and Adam (18). Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Speaking with Ziad, who is the director of the Al-Mawasi Agricultural Association, it is immediately clear – even over a crackly phone line – that he is a man of uncommon energy and purpose, who feels deeply connected to Al-Mawasi.

Established in the early 2000s in response to Israel dismantling 21 settlements in Gaza, the Al-Mawasi Agricultural Association was created to promote and facilitate farming and fishing in the area – which had previously been allocated for the exclusive use of Israeli settlers. Ziad joined the association fresh from university and has overseen its steady growth. Now encompassing 122 members, the association has been providing financial empowerment and support to low-income, marginalised, rural families for nearly 20 years.

Ziad joined the association fresh from university and has overseen its steady growth

“Much of our work centres on women and young people,” he explains. “For example, we established a kindergarten to give the children of fishermen and farmers better access to education and to play. We also run activities designed to build the children’s key skills, so that they have alternatives to working on the farm or at sea.”

The association also opened a clinic where pregnant women could receive specialist care. In general, it has created a range of spaces for women and young people, who are often excluded from decision-making processes in Gaza.

“Challenging existing traditions and cultural habits has been difficult at times”, says Ziad. “However, through local committees, we have sought to change traditional mentalities, encouraging men to accept that women also have the right to actively participate in decision-making.”

Ziad loved his work.

“I am very active by nature, so I was happy to dedicate my time and efforts to helping the members of my community, serving them and caring for them. My ambition was simply for them to succeed.”

The day that life stopped

Everything changed on the morning of 7 October 2023.

“We were getting the children ready for school – I remember, it was 6:15 in the morning – when we suddenly started hearing the sound of bombs,” recalls Ziad. “It was like doomsday: life has stopped since then. At 6:15 in the morning on 7 October 2023, life as we knew it stopped.”

“It was like doomsday: life has stopped since then”

That day, Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups attacked Israeli communities and military bases in the Gaza periphery, killing approximately 1,200 people and taking some 250 hostages. In response, Israel initiated one of the most destructive military operations in modern history, beginning with a bombardment across the length and breadth of the Gaza Strip. This was soon followed by a large-scale ground invasion.

Between 7 October and 20 December 2023, the Gaza Health Ministry reported that at least 20,000 Palestinians had been killed. By the end of December, almost 70 per cent of Gaza’s housing stock had either been damaged or destroyed. In addition, early in the operation, Israel issued a series of “evacuation” orders, forcing more than one million Palestinians from the north of the Gaza Strip to move, with just 24 hours’ notice, to areas further south where little or no aid was available.

“They arrived with nothing, and they didn’t know where to go”

Many headed for Al-Mawasi, which was initially declared a “safe zone” by the Israeli military.

“Since the very first week of the war, displaced people from the north of Gaza have been arriving in Rafah and Al-Mawasi,” says Ziad. “They arrived with nothing, and they didn’t know where to go.”

Preserving human dignity

The Al-Mawasi Agricultural Association immediately mobilised in response to these events.

“My staff and I met the displaced people on the main street, even when it was late at night. They were terrified and panicked from the Israeli bombing.” recalls Ziad.

“We tried to help them as much as we could, directing them to shelter and providing them with electricity and water. Indeed, we hosted around 60 families in the association’s main building for about seven months, without charging any fees.”

“To provide others with safety and shelter is part of what makes us human”

“We had requests from other organisations to rent the space, but we preferred to keep it for the forcibly displaced families,” Ziad explains.

“In addition, we also hosted displaced families on 20 dunams [20,000 square metres] of land belonging to the association. I believe in the teachings of the Prophet to have mercy on those who are in need or distress. This allows us to preserve a sense of human dignity: to provide others with safety and shelter is part of what makes us human.”

This massive influx of internally displaced people rapidly outstripped accommodation supply in Al-Mawasi. Individual families, community-based organisations and NGOs began a desperate effort to source shelter. Empty buildings of all kinds were immediately filled, while already inhabited homes throughout southern Gaza swelled as families opened their doors to extended family members and strangers alike. Ziad himself hosted 35 displaced relatives at his home.

Still, this was not enough. For many families, makeshift shelters were the only option. Lacking the material to construct regular tents, association members raced to create shelters from whatever else they could find.

“A family of 20 would be staying in a shelter of nine square metres”

“We made almost 1,000 canopies out of worn nylon and unused wood that were intended for our greenhouse rehabilitation programme,” says Ziad.

Such shelters helped keep Palestinians alive, but the conditions were extremely difficult. “A family of 20 would be staying in a shelter of nine square metres,” he says.

Famine and disease

At the beginning of its military assault, the Israeli government declared a “complete siege” on Gaza. It cut off water and electricity to the enclave, as well as shipments of food, fuel and medicine. “We are fighting human animals,” announced Israel’s Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, “and we must act accordingly.”

As you might expect, the impact of this siege on the civilian population of Gaza has been devastating.

“At the beginning of the war we had access to electricity,” says Ziad, “but as time passed, this dwindled. We also didn’t have any solar panels, and we couldn’t fuel the generators as the crossings into Gaza were closed.”

According to UN experts, by January 2024, the lack of available food meant that every single person in Gaza was experiencing a state of extreme hunger. Even when food could be found, inflated prices put it beyond the reach of most residents.

Every single person in Gaza was experiencing a state of extreme hunger

“In November and December, the situation became increasingly difficult as food was very scarce,” Ziad says. “We didn’t really have anything to eat, except perhaps a loaf of bread, which we divided throughout the day. A 25 kg bag of flour suddenly cost 200 dollars.”

“And often only one area at a time would have water, so the queues were extremely long and we would have to carry the water from one place to another, which was hard work. Sometimes we didn’t shower or change our clothes for four days.”

To compound the suffering, winter had now arrived, with temperatures plummeting and seasonal rains flooding displacement sites and turning the ground to mud.

With more than one million displaced Palestinians crammed into makeshift shelters without adequate food, heat, hygiene facilities or medical care, disease tore through the Gaza Strip over the winter. According to the World Health Organization, between 16 October 2023 and 13 February 2024, there were 312,693 cases of acute respiratory infections in Gaza, 222,620 cases of acute diarrhoea (117,989 of which involved children under five years old) and 74,712 cases of scabies and lice.

Six months later, and more than ten months since the beginning of the war, the situation for Palestinians in Gaza is a hellscape.

According to the Ministry of Health in Gaza, as of 21 August 2024, at least 40,223 Palestinians have been killed and nearly 93,000 injured since the beginning of the hostilities. An estimated 1.9 million people (90 per cent of the 2.1 million Palestinians currently in Gaza) are internally displaced.

An estimated 1.9 million people are internally displaced

Although some humanitarian aid has been able to enter the enclave, it is woefully inadequate to meet the vast and growing needs of a population subjected to months of unrelenting violence and unimaginable suffering. To compound this, a range of factors, including lack of available fuel and the deteriorating security situation, hamper the ability of humanitarian organisations to distribute what little aid there is. As a result, Gaza faces the risk of famine, with the IPC reporting that 1.1 million people in the enclave are experiencing catastrophic levels of food insecurity.

“I expected at the beginning of the war that things would be bad, but we didn’t expect it to last this long”

“Everyone is very frustrated,” says Ziad. “We are now living on 10 litres of water for drinking, 10 litres for bathing and one meal a day. I expected at the beginning of the war that things would be bad, but we didn’t expect it to last this long.”

NRC’s partnership with Al-Mawasi Agricultural Association

NRC first learned of the association’s role in providing relief to the local community when forcibly displaced NRC staff received support from Ziad and his colleagues in late December.

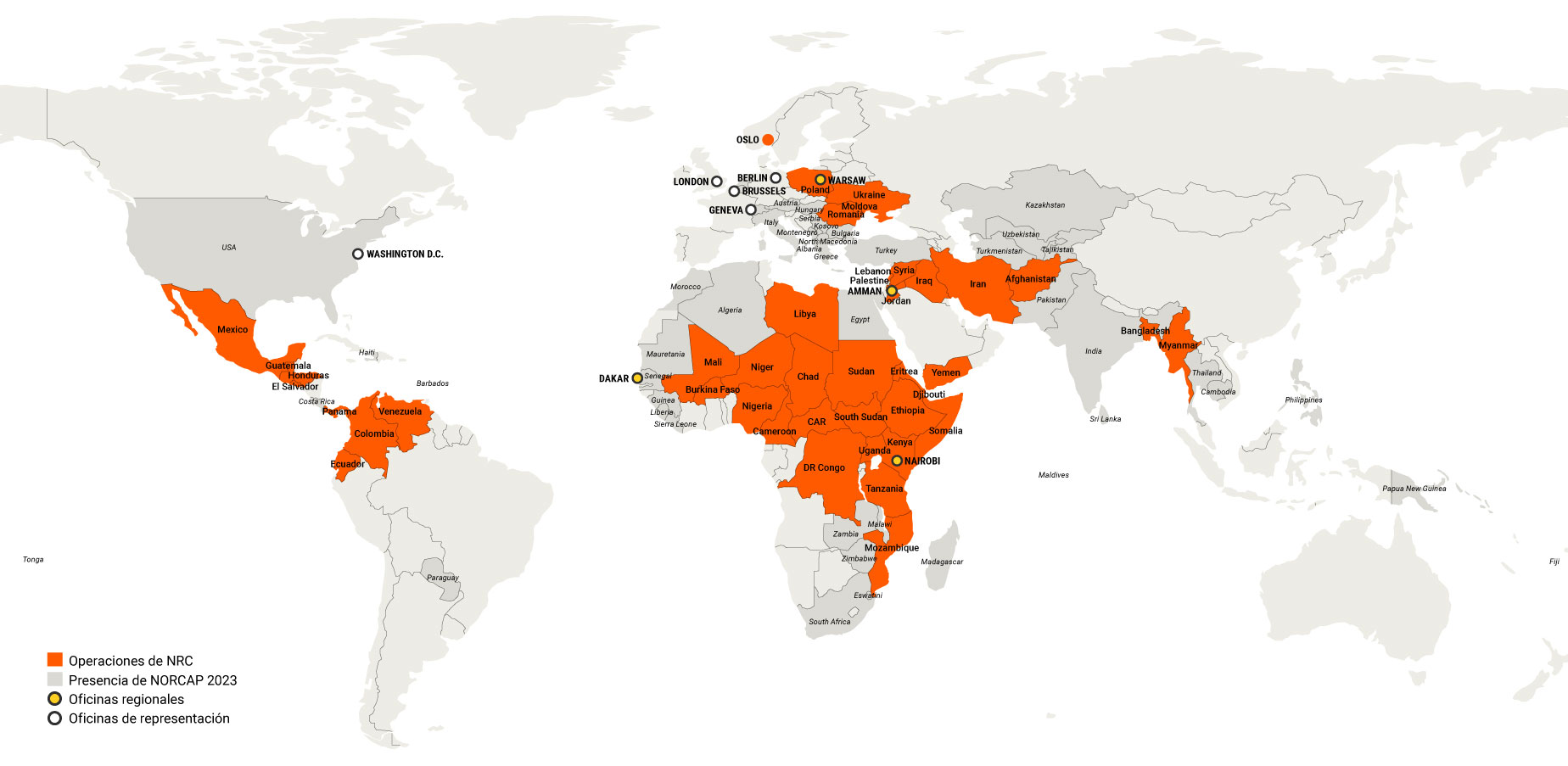

In February, NRC and the Al-Mawasi Agricultural Association became partners, starting an initiative to provide aid to displaced families in the Philadelphi Corridor, a thin strip of land stretching for roughly 14 kilometres along Gaza’s southern border with Egypt.

“It was a major achievement for us to serve so many families in need”

The association proved to be an essential link, helping NRC to identify those most in need, as well as providing warehouse capacity. The association distributed nearly 14,000 relief items, supporting thousands of forcibly displaced people.

“We were able to provide each family with a package including nylon shades, mattresses, a metal water pot, hot water bottles, kitchen equipment and blankets,” explains Ziad. “It was a major achievement for us to serve so many families in need.”

However, Israel has since imposed further restrictions to prevent humanitarian organisations from moving sufficient aid into Gaza, and to safely distribute it once inside. This has brought aid operations in the enclave to a virtual standstill.

“We just do not have the capacity to meet everyone’s needs,” laments Ziad. “The number of people receiving aid is limited. And our own safety is at risk while we attempt to help people.”

Gaza has become the most dangerous place in the world for aid workers

Indeed, according to the International Crisis Group, between 7 October and mid-July, the Aid Worker Security Database recorded 364 violent incidents involving aid workers in Gaza. The UN has reported 289 aid worker deaths. As such, Gaza has become the most dangerous place in the world for aid workers.

“I have lived the experience on my skin”

Even while Ziad and his colleagues were undertaking aid work, they themselves were driven from their homes: their property has been destroyed, their community has been torn apart and their lives have been completed upended.

“When the Israeli army entered Rafah in May, danger finally reached my house and I too was forcibly displaced,” recalls Ziad.

He fled, one of the last people to leave Rafah in a forced exodus of more than one million people. He now lives in a friend’s tent in Deir al-Balah, a coastal neighbourhood in central Gaza. Separated from his wife and children, who are displaced elsewhere in Gaza, Ziad has to deal with an additional layer of fear and anxiety due to loss of contact with family and friends.

“My empathy for displaced people has increased even more,” he says. “I have lived the experience on my skin.”

In fact, we may not understand the hostilities’ full impact on Palestinian society for some time.

“People are now numb to the sound of bombs”

“People are now numb to the sound of bombs,” Ziad tells us. “Everyone has lost weight. Social relationships have totally disintegrated due to the forced displacement. People can’t tolerate being around each other anymore.”

At this point, the phone connection finally fails. When NRC reconnects with Ziad two days later, on 13 June, he is a different man. Gone is the tangible energy, replaced by a bone-deep exhaustion.

“I just found out that my house has been bombed,” he mutters, utterly broken.

An international failure

In Gaza, ordinary Palestinians like Ziad have shown extraordinary resilience and adaptability in the face of unspeakable horror. But everyone has a breaking point. Moreover, this astonishing level of fortitude risks obscuring a fundamental truth: no person – man, woman or child – should ever have to face such horror.

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

The ruins of the Gaza Strip are both a humanitarian catastrophe of unimaginable scale and a testament to the international community’s failure to address the broader “Palestinian question”. While the events of 7 October triggered the current hostilities, the root causes of this crisis lie in Israel’s ongoing belligerent occupation of Palestinian territory and a history of serious violations of international law, including annexation of West Bank land and the blockade and closure of Gaza.

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Israel’s opposition to Palestinian political independence and sovereignty coupled with its rejection of various peace initiatives have resulted in an entrenched model of subjugation, domination and exploitation. International focus on direct bilateral negotiations as a solution to the conflict, to the effective exclusion of all others, has created an environment in which Israeli violations have flourished, Palestinian rights have been egregiously undermined and human suffering on both sides of the 1949 Armistice Line has reached unprecedented levels.

“Where will I rebuild my life?” asks Ziad.

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

“I think it will have to be somewhere else, not Gaza, because life here has become so difficult and the scale of the reconstruction needed is so massive. I no longer have time to dedicate to rebuilding things. My days are limited, and my children need a future. We are in 2024. We no longer have the strength to live inside a tent.”

“The world’s problems should be fought with education and knowledge, not with weapons”

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Yet, despite the horrors he has witnessed and lived, Ziad refuses to relinquish his humanity.

“My message to the world, as Ziad al-Nada, is that we must maintain a decent life despite these challenging circumstances. We need support and assistance to do this, to continue to live our lives with dignity. We want to raise our children and eventually see them in positions of authority, offering the nation different options to what we have today.”

“The world’s problems should be fought with education and knowledge, not with weapons.”

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada

Ziad’s home before and after the bombing. Photos: Ziad al-Nada