The FARC leader is far from satisfied with the government’s ability to implement the peace agreement. He will focus on the settlement as well as the Constitutional Court’s decision that no longer requires third party actors, like politicians and businessmen, to show up in court for war crimes committed during the armed conflict. It’s common knowledge that the powerful in Colombia have used armed groups to kill people standing in the way of their interests.

Timochencko believes the Constitutional Court’s decision goes against the intention of the peace agreement. But others will say that the FARC commanders got off the hook with only eight years in prison.

Failure to integrate former soldiers

In 2016, President Santos received the Nobel Peace Prize and was celebrated in international media. But shortly after, the peace agreement met resistance led by former president Uribe.

President Santos has pushed forward a number of legislative changes necessary to continue the peace process, but implementation of efforts to demobilise former FARC members were delayed, and very little was done to make designated demobilisation zones habitable for residents. A lack of housing, medicine and in some areas, food, led to many frustrations.

According to the UN, just under half of the 8,000 disarmed FARC soldiers still live in these zones. Many have joined other groups because the government has failed to reintegrate them to civilian life.

Civilians being killed

Another major challenge lies in the safety concerns in former FARC-controlled areas. Here, the guerrilla movement the National Liberation Army (ELN), various paramilitary groups and criminal gangs have threatened civilians. UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, recently said that they see a pattern in the killings of local leaders, something the Colombian government has denied repeatedly. But civilians have been threatened and murdered since the conflict broke out 50 years ago.

A number of people have been killed in former FARC-controlled areas since the peace agreement was signed. Many victims include Afro-Colombian local leaders and indigenous peoples. Between 78 and 89 local leaders have been killed in the Pacific area alone this year, according to UNHCR.

Many fear that lack of security and the fight for control over territories between different armed groups will force more people to flee. In 2016 alone, when the parties signed the peace agreement, the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that violence forced 171,000 people flee their homes.

Continuation of drug trafficking

Coca production is increasing dramatically in Colombia and has doubled since 2013, according to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). This pinpoints the need for agricultural development to combat drug trafficking.

The peace agreement promises subsidies to coca farmers who cultivate other crops. But this is only possible if paramilitary and criminal gangs are stopped from taking over new areas.

Drug policy is also a sensitive issue in the Colombian government’s relationship with the United States. President Santos stresses that the international community must find other strategies to combat drug trafficking than the current repressive methods. The war on drugs has caused more harm than good, according to Santos. In response, the Trump administration has threatened to cut its support.

An unstable neighbour

The tense situation in Venezuela can also hamper peace efforts in Colombia. The conflict in the neighbouring country has caused hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans to enter Colombia. Many also fear that the country’s relationship with Venezuela will dominate the presidential elections in 2018.

After 50 years of an armed conflict that has killed 260,000 people and forced over seven million to flee their homes, Colombia’s reconciliation process is facing major challenges. What Colombia needs now is to tackle internal challenges like corruption, impunity, following up on the peace agreement and the return of millions of displaced people.

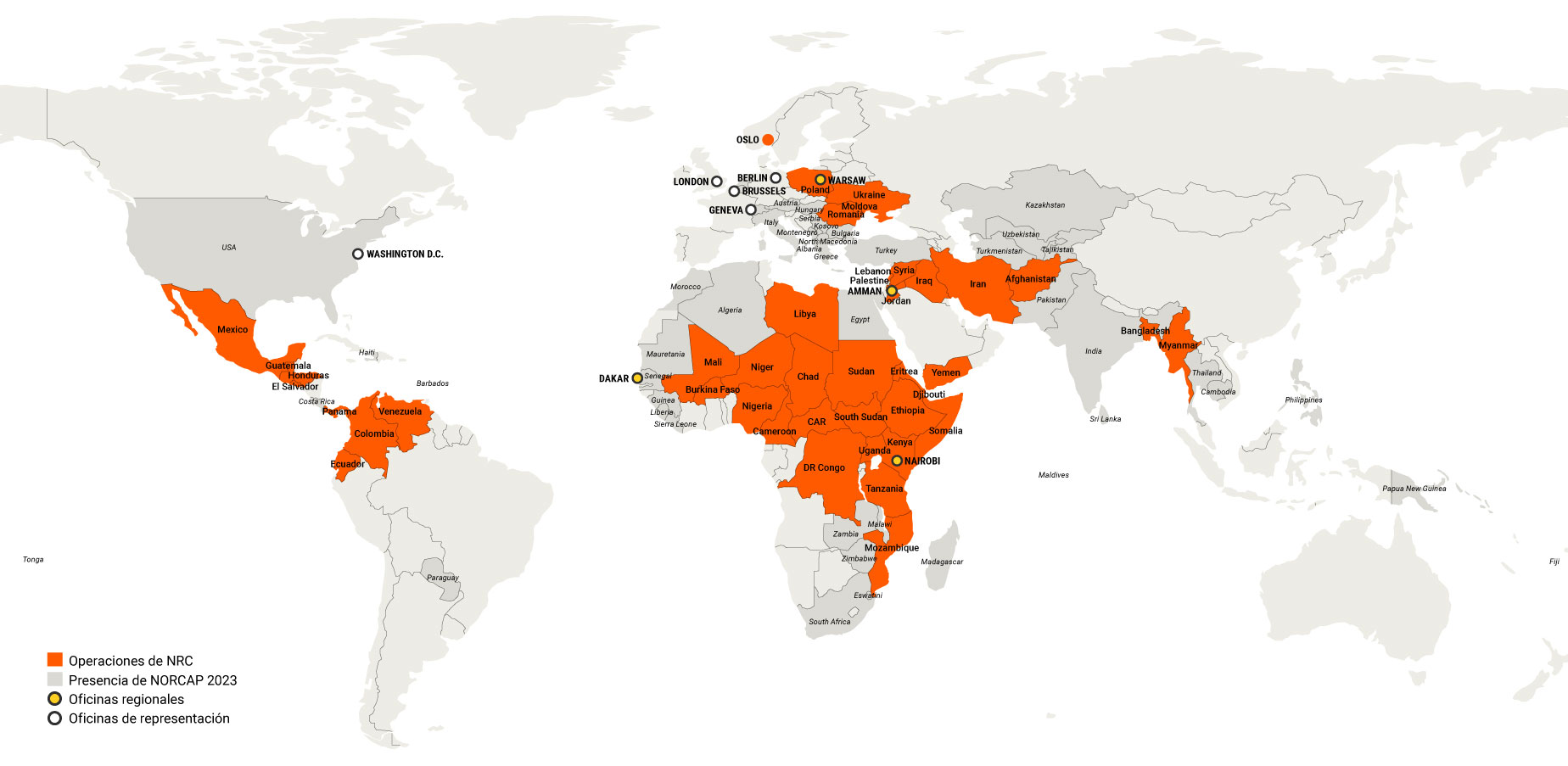

Read about the Norwegian Refugee Council’s work in Colombia.